Back in September, the Indianapolis Star was the first publication to report on sexual-abuse allegations made against Larry Nassar, then a physician and faculty at Michigan State University. In their initial story, two women claimed that Nassar had sexually assaulted them when they were young teenage gymnasts while he was treating them for pain and injuries sustained while practicing gymnastics.

Since that story was published, more than 100 women have come forward alleging that Nassar had also abused them. State assault charges have been filed against Nassar in Michigan and the former physician—his medical license was revoked in April—has pleaded guilty to three federal charges related to possession and receipt of child pornography. (He has pleaded not guilty to the sexual-assault charges.)

Thousands of articles about the assault allegations against Nassar have been published since the Indianapolis Star first broke the story. Almost all of them have used some variant of the phrasing “under the guise of medical treatment” to describe how Nassar gained the trust of these women and girls and abused them, sometimes for years and sometimes without them realizing that something criminal had happened to them.

So far, however, Larry Nassar’s abuse has mostly been talked about through the lens of sports: He worked with gymnasts as a doctor for over two decades, and the vast majority of the former patients who have come forward with allegations were gymnasts. Nassar derived a lot of authority and power from his connection with USA Gymnastics. He was known in the community as the doctor of the Olympic teams. Victims spoke about how they felt it was an honor to be seen by him because of his work with the national team. And the sport enabled him to gain access to young, unknowing victims who were desperate to be relieved of pain in order to train and compete.

This has all been very well-documented in the months since the news about the abuse allegations broke. And USA Gymnastics has—quite rightly—come under fierce attack and a barrage of lawsuits for how it enabled emotional abuse and mishandled the reporting of sexual abuse allegations against professional members.

But Nassar derived his authority from another powerful institution: the medical establishment. To understand how Nassar was able to abuse so many for so long, you also have to consider his role as a physician. Almost no one in society is accorded the kind of trust that we accord physicians automatically.

“We are so reliant on them, we are so helpless and vulnerable and literally in pain often times when we go in there,” said David Clohessy, executive director of SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests) in an Atlanta-Journal Constitution investigation into doctor sexual abuse published last year. “We just have to trust them.” Taken together, the vulnerability of young athletes and the implicit trust we place in doctors have resulted in one of the worst sex abuse scandals in U.S. sports history.

But not necessarily the worst in medical history. There is, unfortunately, a lot of competition for the “most sexually abusive” title among doctors. The AJC noted that victim tallies for doctors were among the highest of all sexual offenders, climbing into the hundreds and even into the thousands. Earl Bradley, a former pediatrician who operated in Pennsylvania and Delaware, drugged young children with doped-up lollipops. He then sexually assaulted them on video. Bradley was charged with 471 counts of molestation, rape, and assault, though he is believed to have assaulted more than 1,000 children. Bradley is currently serving 14 life terms plus 165 years without parole.

The rest of the article is a gruesome litany of assault charges against doctors. In one case, the John Hopkins Medical System settled with 8,000 women for $190 million for the abuse of one its doctors who photographed them during pelvic exams. The doctor in question, Nikita Levy, committed suicide.

Some of the abusers are among the most prestigious physicians in the country. Because of their standing in the medical and wider communities, individual allegations and claims are often brushed aside and the doctor is allowed to keep practicing. What it often ends up taking to stop an abusive physician, according to the AJC, is the accusations piling up—ala Bill Cosby—or a very prominent patient coming forward.

It actually took both of these phenomena to stop Nassar: more than one victim, and a prominent victim. Last summer, the former physician was hit with nearly simultaneous blows. One victim went to the police; the other filed a suit in civil court. Rachael Denhollander, a former club gymnast from Michigan, went to the MSU police alleging that Nassar had assaulted her when she was 15 under the guise of medical treatment in 2000. And 2000 Olympic bronze medalist Jamie Dantzscher (then identified as “Jane Doe”) filed a lawsuit, alleging that USA Gymnastics’ team doctor had assaulted her repeatedly from the time she was 14 or 15 until she graduated from high school while she was competing on the national team. These two women opened the floodgates. Since the fall, more than 100 women have claimed to been abused by Nassar under the guise of medical treatment.

But at first, when the tally of alleged victims stood at “just” two, plenty of people rose up to defend Nassar. In the school board election in Holt, Michigan, Nassar received 21% of the vote—2,730 votes—two months after the abuse allegations had been made public. It wasn’t until the discovery of child pornography on his hard drives, confiscated by the FBI, that the remaining doubters were quieted.

This is certainly in keeping with what the AJC found in its investigation. “Case files from around the country describe doctors who were accused in open court of abusing multiple patients, but still so valued or beloved that other patients rose up to fight sanctions with petitions and even a T-shirt campaign,” Ariel Hart wrote.

While it does seem probable that Nassar will spend considerable time in prison for his alleged assaults on patients, this is hardly the norm when it comes to physicians who have been accused of sexual misconduct with their patients. In fact, what prompted the AJC’s investigation into doctor sexual abuse was this disturbing finding: Two-thirds of doctors in the state of Georgia who had been disciplined for some form of sexual misconduct were still practicing.

“Physician-dominated medical boards gave offenders second chances. Prosecutors dismissed or reduced charges, so doctors could keep practicing and stay off sex offender registries. Communities rallied around them.”

This probably sounds familiar to anyone who has been following the Nassar case. When, in 2014, Nassar was accused by an MSU graduate student of molesting her during a treatment session, a Title IX investigation conducted by MSU cleared him of any wrongdoing due largely to the testimony of other doctors who were longtime associates of Nassar. His doctor peers protected him. Brooke Lemmen was one of the experts on the Title IX panel that cleared Nassar in 2014. She had actually been recommended by Nassar to review that case. Later it was revealed that Lemmen removed documents from Nassar’s MSU office at his request after he was suspended by the university in late 2016; she resigned before she could be fired by MSU.

That 2014 investigation that cleared Nassar led to new requirements for Nassar: that he be chaperoned by another MSU staff member when performing procedures near a sensitive area, that he wear gloves, and that he fully explain the procedure before proceeding.

The private recommendations in Nassar’s file did not stop him from abusing other patients. When he was informed that MSU would be terminating his employment after news of the allegations hit the media, they cited his failure to comply with the requirements put in place after the 2014 investigation.

As was the case with USA Gymnastics and its failure to enforce its own anti-abuse policies, the staff at the sports medicine clinic at MSU was also allegedly negligent when it came to supervising a doctor about whom suspicions had already been raised. (This is why MSU is a party to many of the Nassar lawsuits.)

The AJC found that of the 100,000 physicians in California—there are approximately 900,000 doctors nationwide—anywhere from 500 to 600 are on probation at any given time. And between 2011 and 2013, one in six of those on probation had previously committed another violation. A doctor’s probationary status is generally not disclosed to patients (California is attempting to make this information public, but, as the article highlights, it’s not easy for patients to find this information.)

Safe Patient Project, a patient advocacy group, attempted to get California’s medical board to make physicians tell patients if they’re on probation and what the offense was, but the board rejected this proposal unanimously. The reason: disclosing this information would damage the formation of a healthy doctor-patient bond.

Isn’t that the point, though? Do we really want physicians who exchanged prescription pills for sex or touched patients inappropriately or assaulted them to be able to form strong bonds with new patients? Isn’t that called grooming?

The case of Larry Nassar is not the story of a doctor who happened to abuse gymnasts in his practice. Just as it would be too simplistic to view this story solely through the lens of sports, it would also be incorrect to say that the gymnastics world was simply the setting in which an abusive doctor operated. Sports and medicine feature inherently unequal power dynamics; the relationship between a notable and powerful figure in gymnastics and an athlete, like that between a doctor and a patient, puts one person in control of another by definition. The precise point where these two sorts of relationships overlap creates clear potential dangers, especially in a sport in which athletes are exceptionally young. In retrospect, what’s unbelievable is how little the institutions of MSU and USA Gymnastics did to guard against the possibility that an abuser might take advantage of this unique opportunity to groom and exploit victims.

First of all, it’s impossible to separate Nassar from gymnastics. He was never just a doctor; he was always a gymnastics doctor, even before he was an actual physician. In the Facebook post he wrote announcing his “retirement” from USA Gymnastics in September 2015—it would later be revealed that USA Gymnastics had fired him and reported him to the FBI—he noted that he started working with gymnasts as a trainer all the way back in 1978 when he was still a student in high school. (Nassar even claimed to have received a letter with the women’s gymnastics team for the work he did.) By 1986, he was working with the national team at various competitions. Before he even set foot in osteopathic medical school, he was a well-regarded caretaker figure in the sport.

He continued working with gymnasts while he was in medical school. “Well I could not just go to medical school. I would go to John Geddert’s gym every day. I would volunteer at his gym 20 hours a week and then provide coverage at gymnastics meets on the weekend,” he wrote in the 2015 Facebook post. And it was during this period, when he was volunteering his time—and failing his med school classes as he noted in the post—that he was picking up his earliest known victims. In April, one woman came forward and alleged that Nassar had abused her while he was still in medical school. She claimed that in 1992 or 1993, the doctor-in-training invited her to his apartment to participate in a study. She was between the ages of 12 and 14 at time. She has alleged that Nassar offered her a full body massage for her participation in his “research.” It was during this massage that Nassar allegedly penetrated her with his fingers. This woman claimed that other girls participated in this so-called “study,” which means there are probably more victims from this particular time period who haven’t opted to come forward.

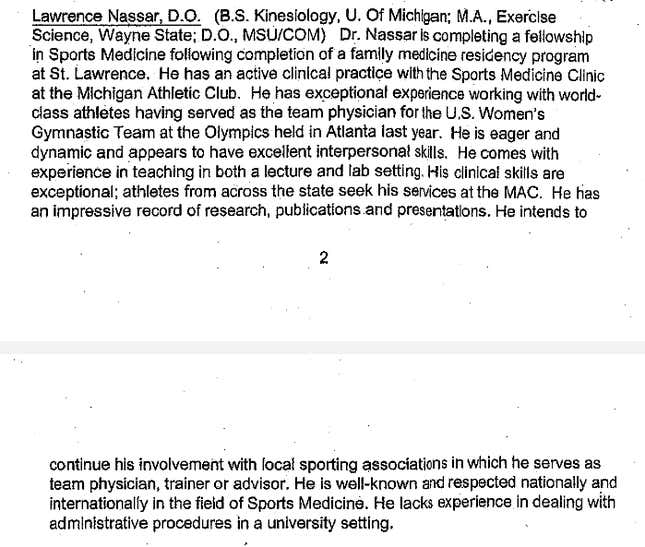

And Nassar’s involvement in gymnastics was a boon to his career as it was getting off the ground. After he completed his residency and fellowship, he applied for a job with MSU in 1997 to become faculty in the Department of Family and Community Medicine and his experience working with the Olympic team—this was only a year after he was the team doctor for the Magnificent Seven—was invoked by the hiring committee in their recommendation. “He has exceptional experience working with world class athletes having served as the team physician for the U.S. Women’s Gymnastics team at the Olympics held in Atlanta last year,” the committee wrote. Later, the committee noted that due to his athletic training experience, Nassar brought more experience than most young applicants would bring to the position. And finally, his publication and presentation record—almost all about treating gymnasts—outpaced his competition for the position. Nassar was offered the position and worked at MSU until he was fired in September 2016 after the first round of allegations were made public.

His “volunteer” work with USA Gymnastics was encouraged by his employer, MSU. Depending on the year, anywhere from 50-70% of his time was supposed to be devoted to “outreach,” which included his work at local gyms in Michigan and with the national team gymnasts. In his 2013 performance review, his “outreach” was held out for special praise:

“This is the area that you are truly exemplary. You continue to work at Twistars Gymnastics and Holt High School not only covering events but also with regularly scheduled clinics for the communities involved. You have been the medical director of USA Gymnastics and provided coverage for the USA at the 2012 Olympic Games.”

Nassar’s employers saw his work with the world’s best-known gymnasts as a boon to their institution. Former MSU gymnastics head coach Kathie Klages highlighted Nassar’s work with the team during her recruitment of athletes. (Klages retired after being suspended by MSU when it was revealed that she failed to report allegations made against Nassar going all the way back to the late 90s.) And having a renowned MSU physician working to care for the team at camps and competitions was certainly a bonus for USA Gymnastics. The two institutions mutually reinforced Nassar’s authority and power.

And if Nassar wasn’t simply a doctor who happened to abuse gymnasts, his victims weren’t simply patients who happened to be gymnasts. Their athletic pursuits added a unique dimension (and vulnerability) to their status as patients. They weren’t just coming to seeking his care and expertise to be relieved of pain and to heal injuries as a non-athlete patient would; they were there so that he could help them return to a sport that, for many of them, was their whole life. Maybe they were trying to make the Olympic team. Or maybe they were vying for a college scholarship. Or maybe they were simply hoping to move from Level 7 to Level 8. Regardless of the ambition, gymnastics meant a great deal to them, and the prospect of missing practice and competition was daunting for many of them.

Nassar knew what was at stake for his athlete-patients. And, after having spent so many years in gyms, he understood the environment well: the pressure, the harsh coaching practices. Many victims said that Nassar also acted as a trusted confidante, a person to whom they could speak about their troubles in the gym and with their coaches.

In his role as the doctor of the national team, he held even more power over his patients. The gymnasts he treated at the Karolyi Ranch and on the road while competing had invested more time and effort into the sport than almost anyone else. This level of investment made them the most vulnerable to abuse of all athletes. “We often find abuse is most likely to happen to these people who are just about to or have made [it] to the big time,” Daniel Rhind, director of the Brunel International Research Network for Athlete Welfare, told me. “They’ve invested a great deal and they’re probably in their most vulnerable [state]...They inevitably don’t want to tell people or when they do tell people, they’re not believed.”

They were also captive in a sense. At home, the gymnasts and their parents could select doctors. But at camps or on the road for meets, Nassar was it. And he didn’t necessarily work for them. Nassar was selected by USA Gymnastics. Were the treatment decisions he made always in the interest of their well-being? Or were they made on behalf of USA Gymnastics?

In her GymCastic interview, 1997 co-national champion Vanessa Atler talked about being at the 1999 world championships in China when Nassar entered the room with Muriel Grossfeld, asking who wanted a cortisone shot. Atler, though she was injured, refused. She said that she felt judged for refusing, that they viewed her as a wimp. “It’s weird the way they come onto you to make you feel bad about the decisions you make just to get you go and compete,” Atler said.

Kristen Maloney, the 1998 and 1999 national champion, who was also injured, accepted the offer, according to Atler. In an email, Maloney didn’t dispute Atler’s account though admitted that her memory of the event was not perfect. “I’m pretty positive I did get one,” she wrote. “I was in a lot of pain, shin-wise, at that point.” She also noted that the shot might’ve been lidocaine, not cortisone.

Maloney, who was 18 at the time, was known for being exceptionally tough during her gymnastics career. She competed through several painful injuries to make the 2000 Olympic team. This year, she spoke with ESPN about all of the injuries and pain she had endured and how she would have done basically anything to get to the Olympics. She was definitely the kind of athlete who would consent to a shot of cortisone to help her compete with an injury at a major competition.

In offering it to her, though, was Nassar, as a physician, working in her best interest? Or that of the federation, which really needed her scores?

Last year, the Associated Press surveyed 100 NFL players and found less than half of the players believed that “the league’s clubs, coaches and team doctors have the athletes’ best interests at heart when it comes to health and safety”:

“A couple of players mentioned the ‘conflict of interest’ inherent to a team doctor’s job. One labeled players ‘the asset’ that medical staffs need to rush back as soon as possible. Another said ‘everyone knows’ the quality of care depends on the size of a player’s paycheck.

‘It’s their job to make you playable,’ Detroit Lions safety Don Carey said. ‘There’s a lot of pressure on them to keep guys on the field.’”

One player with an astonishingly clean injury record noted that the reason he had remained so healthy for so long was that he doesn’t rely on the teams he plays for to manage his health care. He takes care of it on his own.

A doctor who is working for USA Gymnastics, or any sports team or federation, will have complicated allegiances, even under the best of circumstances and even with the best of intentions. Nassar, as we have learned, wasn’t working under the best circumstances, and he didn’t have the best intentions.

And unlike an NFL player, who will have the chance to play in several games over the course of a season (or his career), an elite gymnast has precious few opportunities to compete internationally for the U.S. Beyond the Olympics, every year there are just three or four international competitions to which the U.S. sends gymnasts. Being healthy—or at least healthy enough—at the right moment is an important first step to being selected for a major competition.

In 2013, Nassar spoke about the role that health plays in team selection:

“You’re selecting, you’re picking. And now you [the selection committee] want to know their injuries, and every detail about their injuries. And you want me to tell you the details of those injuries, so those weigh into how you select those athletes.”

Can you imagine being an athlete who is being sexually abused by Nassar attempting to report him when he holds all this power over your inclusion on a particular international team? What teenage athlete who has spent her entire life training to compete for the United States would speak up under those circumstances? It would be expecting a great deal—too much really—to assume that a gymnast would come forward against the team doctor, a person who both represents the organization she wishes to compete for and whom her parents told her to trust from the time she was very young.

Gymnasts need doctors; as young people competing in a relentlessly brutal sport, they need them more than nearly anyone else. Moreover, they need their relationships with their doctors to have basically the same features that Nassar so successfully exploited: A gymnast needs a doctor in whom she has trust, in whom she can confide when there is a problem, and whom she regards as her advocate. The solution to the problem of physicians who abuse, whether in sports or anywhere else, can’t be to simply put distance between patients and doctors, any more than it can be to turn to faith healers or Gwyneth Paltrow for healthcare guidance. Whatever else is part of that solution, though—protocols that would raise a flag when a doctor is giving rare and invasive treatments to dozens of teen girls; requiring additional adult supervision during exams and treatments while underage athletes are at the national team training center—the first and most important step is the simplest. In order to best protect and serve the interests of patients, whether they’re athletically challenged or world-class gymnasts, allegations of abuse must be taken seriously. Both USA Gymnastics and the medical establishment failed to do this for years, and the consequences are only beginning to be known.