Protect yourself at all times.

—Anybody who knows shit about boxing

Grand Rapids

You’re born under a state of siege. And not only you: everyone you know, everyone in your neighborhood, lives under a state of siege. And within this state of siege there is a hierarchy of the besieged. In this hierarchy, you begin at the bottom.

It’s the first rule of boxing: protect yourself at all times. When you’re introduced to it, whoever tells you about it will say, “This is the first rule of boxing. Protect yourself at all times.” If something happens to you in the ring, fair or foul, because you weren’t paying attention, it’s all on you; it’s your problem and your fault. Nobody is looking out for your best interests. And nobody owes you anything.

If you were to find yourself in Las Vegas at Floyd Mayweather, Jr.’s gym, you’d see toddlers, battened down with comically oversized boxing gloves, taking unsteady early steps toward veteran trainers with pads or palms held up to receive them. Then you’d see perfectly executed one-twos, rapid fire hooks coming off the jab, and, maybe, the final touch, a straight right cross following on the heels of the hook. The tots would be moving their heads too.

The difference between Floyd’s gym and The Place, the gym in Grand Rapids where he, as a toddler, threw the same perfectly executed combinations, is what was waiting on the other end. At Floyd’s Vegas gym, the guys receiving the infant uppercuts are either millionaires or their hangers-on. Waiting for Baby Floyd was Senior Floyd. And Senior’s response was a sharp return shot, its intention to penalize for a moment’s lapse in concentration. Or maybe just to let the kid know who was the boss.

Babies with aptitude and good boxing pedigrees, made to fight grown men, become defensive wizards. As a child, Wilfred Benítez was rewarded with an ice cream cone if he sparred against adult opponents without getting hit. Is it any surprise that he wound up being called “El Radar”?

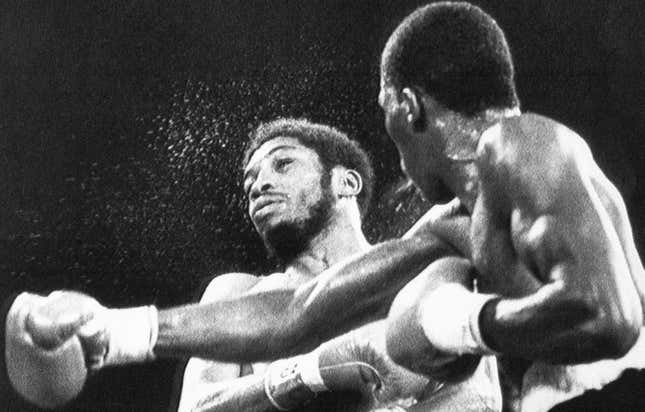

Roger Mayweather vs. Jorge Alvarado, 1983. Photo via AP

The main reason Floyd Mayweather was born to fight is that he was born into a family that was born to fight. His personal aptitude doesn’t come from having unusually fast hands or feet (his impeccable timing makes Mayweather look faster than he actually is, but many fighters, including some of his opponents, are faster of both hand and foot), great punching power (in his prime, he was a slightly above average puncher, and may no longer be that as he becomes increasingly handicapped by bad hands), being a particularly tough guy (Floyd Senior and Uncle Roger are much tougher), or a body that gives him an intrinsic advantage (he’s got a good boxer’s body, but you need only reference photos of Thomas Hearns or Emile Griffith, who both fought at welterweight—Mayweather’s current division—to see what someone with real physical advantages at 147 looks like). Floyd Mayweather’s primary gift is a Mensa-level boxing IQ that combines with an off-the-charts alertness just shy of paranoia. Endlessly watchful, he is a keen reader of body language, including the specifics of the current range of boxing vocabulary; there is nothing that a contemporary fighter can do that he hasn’t seen before. And once he’s got you scoped out, usually a matter of two or three rounds, he knows exactly how to beat you.

Here’s a case in point. The single savviest thing Mayweather has done so far as a pro was to suckerpunch the unctuously eager-to-please Victor Ortiz on a break while referee Joe Cortez was otherwise occupied, knocking him back into the Hollywood dreamland he’d come from. The kayo was one emphatic way to synopsize what Mayweather had learned in boxing and in life, and which Ortiz had failed to.

But he’s had other satisfyingly impressive performances. Facing Zab Judah, who could superficially be seen as a bigger, stronger, faster, harder-hitting southpaw version of himself, Mayweather endured a few rounds of being outdone while making a mental catalogue of his opponent’s shortcomings. Judah’s biggest drawbacks centered on issues of character. He possessed a strange combination of megalomania (a trait he shared with Mayweather) and uncertainty; he was a fighter who became unraveled when things stopped going his way. And, unlike Mayweather, he was incapable of framing a fight in terms of the big picture. Mayweather simply let Judah wind down, then began timing him, peppering him with quick right leads, pulling further and further ahead. Judah started fouling, eventually pointedly delivering a hard one-two, the first way below Mayweather’s beltline, the next to the back of his neck. Time was called by referee Richard Steele, and Roger Mayweather then jumped into the ring in order to kick the shit out of Judah. Both corners both went berserk and engaged in an in-ring tussle that Judah joined. Floyd Mayweather didn’t involve himself, watching bemusedly from a neutral corner. When the fight resumed, he dominated it until the final bell.

There’s some irony in all this. Although he exhibits an appalling lack of character in nearly every other aspect of his life, one of Floyd Mayweather’s most reliable traits in the ring has been his character. Nobody wins 47 times in a row against good opposition without having character; too many things can go wrong in a fight to allow for that. Like all great fighters, Floyd is able to plan an entire full-distance scenario. He can see how the fight is likely to unfold beforehand. He also has the ability to improvise and adjust as needed. Aside from not being a big puncher, there’s nothing that he doesn’t do well in the ring.

Senior’s Big Chance

Although Floyd Senior seems like less of an asshole than his son, he was a much more dangerous person during his fighting days, and likely remains so even at 60.

Thirty-five years ago, immensely talented, but poor and underprepared, he lost by knockout to Sugar Ray Leonard, America’s Golden Boy of the time, and then roiled with a variety of “what if” resentments.

He had done well enough early in the fight, maybe even taking the first couple of rounds. But fatigue set in, cutting into his effectiveness; after the fifth, he could only be aggressive for the first 90 seconds of each round, but then had to absorb whatever Leonard hit him with until the bell. He nearly made it to the end, and probably would have if Leonard hadn’t treated what referee Martin Taber meant to be a standing eight-count as if he had stopped the fight, throwing his hands in the air, dancing an ersatz Ali jig that flattered him neither as hoofer nor athlete, and summoning Angelo Dundee (always quick on the uptake) and the rest of his entourage into the ring. Taber was too intimidated by the lightshow to correct things, Howard Cosell was jubilant, and the network got the result it wanted. Forty-four seconds were left in the fight.

Floyd Mayweather, Sr. vs. Sugar Ray Leonard, 1978

Even today, Floyd Mayweather, Sr. will tell anyone who’ll listen (including Leonard, to his face) that Sugar Ray never beat him. He says he came into the fight with only one good arm, and that Ray’s people knew this beforehand.

It’s possible. Mayweather’s manager/trainer was a guy named Henry Grooms, a big, charismatic former football player with the cultivated baritone of an Arthur Prysock. (“Here’s to good friends. Tonight is kinda special. The beer they pour must say more somehow. So tonight, tonight, let it be Lowenbrau.”)

Over the years, I’ve occasionally crossed paths with Grooms. He trained Mitch “Blood” Green briefly before I managed him, tried to interest me in becoming financially involved with his lightweight Courtney Hooper, and wasted some of my time and money by having me fly Martin Foster, along with two cornermen, to Miami for a fight that he couldn’t deliver.

Grooms would have known that when Sugar Ray Leonard comes knocking at the door, you let him in. Mayweather, Sr. was just another hard-luck fighter, capable of being a top-notch contender or more, but stuck in real-life circumstances that would prevent it. With a guy like Mayweather, you took money fights for him whether he had one arm, two arms, one leg, two legs, one eye, or no eyes. You put money in his pocket and in your own. And you instructed him to throw his hardest punches early, just in case it turned out to be one of those weird nights. If you said no, the matchmaker would simply move down the list to the next talented one-armed fighter.

But it’s easy to see how Senior might have felt he got jobbed. He might have been able to convince himself that, in terms of natural talent, he and Sugar Ray matched up pretty well. That maybe he punched harder. And that, with time to train and two good arms, he’d have replaced Leonard as America’s sweetheart. Fighters tell themselves all kinds of bullshit.

Black Code

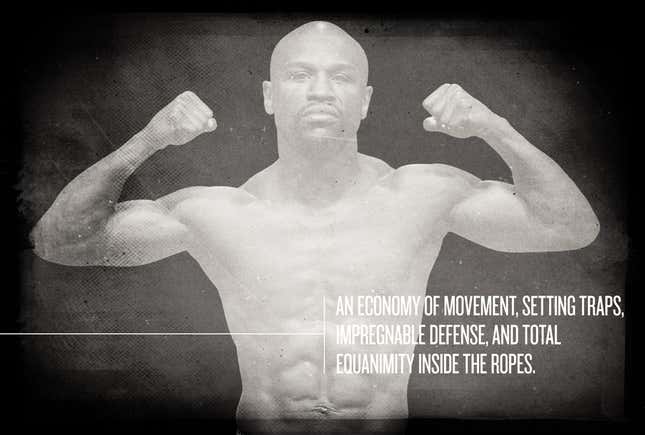

Starting around the turn of the 20th century, and hitting its high-water mark between the 1930s and the 1950s, a coded language of primarily defensive boxing was developed by talented, hard-luck black fighters intent on staying healthy and busy. They innovated and developed techniques that consisted of economy of movement, setting traps, impregnable defense, and total equanimity inside the ropes. They were unflappable. Punching power complicated matters. Some of the best Black Code fighters were punchers: Sam Langford, Charley Burley, Eddie Booker, and Jersey Joe Walcott could all pull the plug on an opponent with one shot. But even those closing-time punches were delivered with a sleight-of-hand nonchalance that belied their monstrous power. Delivered without the exclamation marks that mainstream viewers live for, fans were stuck with the mystery of seeing a fighter upright one second, suddenly and puzzlingly on the deck the next.

Jersey Joe Walcott vs. Joe Louis, 1947. Photo via AP

How was this kind of fighting learned? It was taught in black gyms run by black trainers who’d been fighters themselves. It was picked up being the chief sparring partner of champions you’d never officially fight. It was learned while crisscrossing the country in cars and buses, fighting other black fighters who were crisscrossing the country, taking notes on what had worked and what hadn’t. What emerged was a finely honed style stripped almost entirely of error.

Fighting often, and fighting the cream of the crop, these unwanted fighters developed enormous boxing vocabularies. Whenever they were taken from the orbit of fighting each other, they could beat anybody, even if it was tacitly understood that they would often be robbed in other fighters’ hometowns. (The often-heard phrase was, “If I beat him, can I get a draw?”)

There isn’t film footage for this entire crop of fighters, and some of the best, like Eddie Booker, went unrecorded. Watching even the least celebrated of them on Youtube, though—these are guys with 20 or 30 losses—it’s immediately apparent to anyone not gulled by records that they’re a universe better than almost anyone fighting today.

In the ‘30s and ‘40s, Charley Burley was the best of them, operating at such a level of sophistication that his tricks remained well beyond the ken of most audiences. Burley was held in reverence by his peers, deeply feared and avoided. But he was not terribly popular with fans.

By the time I began managing fighters, what Burley had been able to do had gone from being over the heads of most viewers to being over the heads of most professional fighters.

Once, in a foolish attempt to educate Martin Foster, a naive heavyweight in my stable, I played him a video of Charley Burley handily beating the dangerous Oakland Billy Smith.

Foster watched for a moment, then began to laugh. He was undefeated at the time, although clueless as to why this was the case.

I remember how, as always when watching Burley fight, I was moved to comment. I said something like, He was unbelievable, wasn’t he?

Foster stopped laughing. He was a big white boy who’d been raised on a farm in Kansas, so he had manners.

Sir, I hate to tell you this, but that guy can’t fight a lick. He don’t do nothin’ right.

You’re sure of that, Martin?

Yessir. One hundred percent sure.

What’s he doing wrong?

Well, for one thing, he ain’t hardly fighting at all. They’re mostly just lookin’ at each other. Is that the way guys fought back in them days?

Some guys did.

Is that like in Jack Johnson times? Like when they used to have bare knuckles fights?

No, it’s a lot later than that.

Fighters are a whole lot better nowadays. He nodded solemnly, wise in his pronouncement. I don’t think this guy would last a round if he was fighting today.

Holman Williams in training, 1946. Photo via AP

Black Code is racial, cultural, generational, and economic. It developed as a way of protecting oneself from damage: damage from punches, damage from cuts, and damage from economic loss. It allowed fighters to be in a perpetual state of readiness, willing and able to travel anywhere to fight anyone. Between them, Charley Burley, Eddie Booker, Holman Williams, Henry Hank, Holly Mims, Ralph “Tiger” Jones, and George Benton fought 735 times. Collectively, they suffered eight kayo losses. Keep in mind that, during the eras in which they fought, if a bout was stopped as the result of a cut caused by a head butt, the damaged fighter still lost by TKO. Using today’s boxing rules, those eight kayo losses would have been cut in half. Further keep in mind that these fighters all spent their careers taking on monsters (including often having to fight each other), but that none of them was a world champ. None ever even fought for a title. It’s worth reading that last sentence again and thinking about its implications.

If you add in four of the best black code fighters of the last 30 years—Larry Holmes, Mike McCallum, James Toney, and Bernard Hopkins—to the group, the total number of fights increases to 1021, but the number of collective knockout losses only moves up by one, to nine.

As boxing moved out of the mainstream, as localized boxing lost its cultural currency, as the purses for fighters became more and more polarized, as fighters fought less and less, as qualified trainers dropped off to the point where there were no longer more than a few good ones, and as the marketing of fighters increasingly demanded that they have unblemished records packed with knockouts, the black fighters who spoke boxing’s secret languages dwindled from hundreds to dozens. It has finally trickled down to the last of the tribe: Floyd Mayweather, Jr.

It’s worth considering that none of the other recent masters of the tradition—Toney, Hopkins, Chris Byrd—has been nearly as successful or famous as Mayweather. Neither has anyone else who’s operated with any variation of it. That’s understandable: the style itself is too subtle, its inflections too hidden from sight, to draw any but the most boxing-savvy viewers. Everything about the code resists calling attention to itself. In some ways, that’s its point.

Floyd Mayweather, Jr. has been a mainstream celebrity long enough so that it’s easy to forget that he fought for years as no more than a well-respected champion. His ascendancy came from piggybacking onto the success of Oscar De La Hoya and Ricky Hatton. Mayweather was clearly the B-side of these promotions; the other guys were selling most of the tickets. By beating a retired icon in De La Hoya (who, truth be told, wasn’t nearly as good as he was made out to be), and a popular, but limited light-punching brawler (a style tailor-made for Floyd) in Hatton, Floyd found himself at the top of the mountain. Once there, he talked about it constantly.

And he worked hard at building this persona, which seems to divide people in about equal measure. A fundamentally uninteresting guy with nothing much to say, he has developed a public style that is the near polar opposite of his in-ring one. It centers almost entirely around vulgar displays of excess, mostly financial, occasionally interspersed with pronouncements of maudlin sentimentality. It’s a network TV reality show persona. And, for whatever reason, it has worked.

He Makes Everybody Look Bad: Time Stands Still (For Talented Black Guys)

For a while, before things started to go bad for both of us, I managed a great black fighter who’d been taught the code by another great black fighter, who himself had been managed by a fighter so great that he didn’t need the code, which was the thing that prompted the trainer of my fighter to learn it in the first place. I managed Freddie Norwood, who was trained by Adolf Pruitt, who’d been managed by Henry Armstrong. Fathers and sons, in a way. But remember, this is boxing: beware your father too.

Henry Armstrong vs. Al Davis, 1944. Photo via AP

Trying to deal with matchmakers and promoters for Freddie Norwood was like moving into a time warp, waking up 40 years in the past. Nobody would touch him, even though they understood how good he was.

Bernard Roos was a wealthy Swiss businessman with a hand in promoting boxing throughout Europe, mostly in France. He’d call periodically to see about my sending fighters overseas.

Charles, he might call up and say, could Freddie Norwood be available for Julien Lorcy?

Are you sure you want Norwood, Bernard? I mean, I’m happy to send him, but he’ll destroy Lorcy.

Oh, good God no, Charles. We don’t want Norwood to fight Lorcy. We’d like you to send him over to spar with Julien.

If he spars with him, he’ll hurt him.

Well, tell him not to. We want to build up Julien’s confidence. And he can learn a lot from Freddie Norwood.

You don’t think you could develop a market for Freddie in Europe? He’s the best fighter in the world at anywhere near his weight.

He doesn’t have a style that appeals to anyone. He makes bad fights. And he’s not African, from any of the colonial countries, where people might care about him.

He’s much better than everybody else.

I know. And that’s what makes it so sad. Let me know if you change your mind about Lorcy. We can pay Freddie two thousand US a week, but he’d have to behave.

With Norwood, I got an education on how difficult it is for a black fighter with superb but subtle skills, no cinematic back story, and a less than outgoing personality to make much headway in the business. Nobody wanted him. It was taken as a given that he was the best junior featherweight in the world. This did him more harm than good.

Occasionally I’d get a call from Ron Katz or Bruce Trampler at Top Rank.

I was going to ask if you were interested, but I know you’re interested. Would you put Norwood in with Frankie Toledo at 130? I know he fights at junior featherweight, but I figured you’d spot the weight. It’s for the Friday Night Fights.

Duva won’t take it.

He says they will.

They won’t.

But you will.

Absolutely.

It’s not big money.

We’ll take it.

It’ll have to be at 130.

We’ll take it. Toledo’s people won’t.

Duva says they will.

Book the fight. Want to make a side bet on how long it takes before you call me back?

I know. But they want to see Toledo step up. And they say they’ll do it.

Bet me the amount of Freddie’s purse.

No way. I’ll call Duva and tell them Norwood will take the fight. I’ll get back to you.

I know you will. And I know what you’ll say.

A conversation like that would end with a laugh.

The Freddie Norwood-Frankie Toledo fight never took place. Everyone from both sides knew from the beginning that it never would. Variations on this scenario happened again and again. Some promoter or manage would get brave one morning, decide that their rising star was ready to handle anyone in the division, and figure that having Freddie Norwood’s name on his resume would confer onto him instant credibility. Sometimes this bravery would extend past their morning coffee, and they’d have their matchmaker call me to propose a fight. Inevitably their better judgment would kick in by early afternoon, and I’d get the follow-up cancelation call.

Maybe in six months.

The time isn’t right.

Turns out he’s already signed for another fight.

… sustained an unfortunate training injury ...

Freddie Norwood, 1999. Photo via Getty

Eventually I decided that enough was enough, and made an all-in play to get Freddie onto everyone’s radar. By essentially giving away his services, I nailed down three televised dates on three networks, all within a six-week period—a true old-school move. Through Brad Jacobs, I arranged for the first fight to be on USA’s Tuesday Night Fights against an opponent whom I knew he’d knock out within three rounds. That fight paid $1,500. Ron Katz and I made a deal for him to be on the Friday Night Fights 10 days later against someone he’d beat easily, but might have to go six or seven rounds against. He’d get $3,500. Then I negotiated with Alex Sherer for Freddie to fight three weeks after that at the L.A. Forum Boxing on a show televised by SportsChannel. His opponent for the NABF featherweight title would be Manuel Medina, a former IBF featherweight champion. The winner would be the mandatory challenger for the IBF world featherweight championship, a guaranteed title shot. The 12-rounder paid only $12,500, but it put Norwood where he needed to be. All three opponents were tailor-made for him, especially Medina, whose style was to push relentlessly forward. He wasn’t a hard puncher; he was easy to hit; and he was prone to cuts. His strong suits were his conditioning and his courage. Skinny and sunken chested, he looked frail, but wasn’t. A pro from the age of 14, Medina was never a gifted fighter, but he was astonishingly mentally tough, and he wore down opponents who doubted themselves, guys who were actually better than he was. (I’d learned that the hard way one night, losing a $15,000 bet that Tom “Boom Boom” Johnson would beat him.) Still, Norwood, a man with no self-doubt, would outbox him, catch him coming in, bust him up, then either knock him out or force the fight to be stopped on cuts.

The plan was to make Freddie Norwood the most talked about fighter in the world—to make sure that, when you turned on your TV, there he’d be, knocking someone out. Turn the channel, Freddie would be there. Three televised main events in six weeks. And then a title shot that he would win. With the title would come the paydays. While I was setting the fights up, I didn’t tell any of the matchmakers about the other two fights.

Ron Katz was upset when he finally found out that Norwood was bookending the Friday Night Fights show. He told me that Norwood couldn’t fight on another network so close to his Friday airdate. I never was able to entirely placate him, but he understood that, with what the show was paying and without a promotional contract with Top Rank, it was necessary that Norwood do whatever he could to gain visibility.

I was feeling very proud of myself for my hotshot maneuver, but everything came to an abrupt halt when I called Freddie to tell him the news. I remember outlining the fights, and the reason behind taking them.

Nah. I ain’t fighting for that kind of money.

Freddie, you have to. There’s no choice. The only way you’re going to make money is to win the title. And the only way you’re going to get a shot at the title is if you’re the mandatory challenger. There’s no money until there’s real money. And this is how to get to the real money. Believe me, take these fights and you’ll be the hottest prospect in the world.

I ain’t doin’ it.

Man, you can’t imagine the bullshit I went through to get this set up. Nobody wants to get in the ring with you. So do this thing. In two months, everything will change.

He wouldn’t budge. Our relationship came to an end with that phone call. I felt sorry for myself. I felt sorry for Freddie, too, but I was angry at him. Everything for a fighter like him came the hard way, if it came at all. You had to make your own opportunities.

A little later, I was living on my farm in Las Marias, Puerto Rico. Freddie Norwood called to ask if I’d go back to managing him. He was the featherweight champion at this point, but wasn’t seeing any money. I turned him down. I liked Freddie personally, and he liked me. We’d spent a lot of time together in Brockton, where he was living at Marvin Hagler’s aunt Herbertine Walker’s place while training at the Petronelli gym.

I called my business partner, Pat Petronelli. He’d gone through a hard road with Marvin Hagler, but they’d eventually hit the jackpot. If you were the kind of fighter Hagler was, the kind that Freddie Norwood was, there was only one available path. You never refused a fight. You made every concession you had to. You went anywhere for a fight. You took preposterous paydays. You shamed the other contenders into fighting you. You beat them all until you were the last man standing. Then they came to you.

Months earlier, Pat Petronelli and I had watched Norwood hitting the pads with Adolf Pruitt and sparring with Edgar Santana or Pito Cardona.

Pat would laugh and say, We come up with another one, Charles. Uncrowned champion. Look at how little Freddie keeps that little head tucked in real good. It’s like a little peanut. Nobody can reach him with nothing, Charles. Believe me, nobody’s going to beat this kid.

And, for many years, nobody did. Not even Juan Manuel Marquez, much to the suits at HBO’s dismay. By the time Freddie Norwood beat Marquez, giving the mainstream public got its first look at him, he was nowhere near as good as he’d been at junior featherweight, training daily under the endlessly watchful Adolf Pruitt.

There was nowhere for him to go but down. So that’s where he went.

Nothing New Under the Sun: The Shoulder Roll

Floyd Mayweather, Jr. gets so much credit for the shoulder roll that one might assume he invented it. But the shoulder roll has been around a long time, and a lot of guys were more adept at it than Mayweather. Mayweather uses the shoulder roll to slip a punch and then counter. That’s it: basically a simple two-part deal. In its monochromatic misapplication by younger fighters copying Mayweather’s version, it has become a surefire knockout loss device. But the shoulder roll, properly utilized, had great value at one time. Henry Hank, a middleweight seen as no more than a tough gatekeeper during the ’50s and ’60s, executed a far more sophisticated one. He used it to slip and counter, too, but he also misdirected with it, led his opponent around with it, threw punches from both sides off of it by pivoting his own body, and conned his opponent to try to headhunt as he ducked and dodged. Watch for yourself.

This Business of Being Undefeated

Generally speaking, Black Code fighters are not well liked by the public. A few of them have come up with ways to jazz up their presentations to become more fan-friendly. And some of them were such good punchers that, even while maintaining a conservative style, they knocked opponents out in highlight reel fashion.

But inside the ring, Floyd Mayweather, Jr. is an unembellished fighter who, these days, knocks no one out. His unprecedented market value comes more from his mouth than from his fists; his slogan of “the best ever” can gain currency only with an audience that didn’t come up seeing legitimately great fighters, and doesn’t quite have the critical thinking needed to assess greatness. Floyd has hammered home his point about being undefeated so relentlessly that boxing fans have bought it. Being undefeated for nearly 19 years must make him the greatest fighter ever. Or at least one of the top two or three.

Floyd Mayweather, Jr. vs. Canelo Alvarez, 2013. Photo via Getty

But being undefeated can be misleading. It always means something, but what it means can vary widely.

There are ways that you can keep almost any fighter undefeated for a long period of time. And there are managers and promoters who will do that, especially with heavyweights, expressly for the purpose of cashing them in for big money somewhere down the line. That they’re undefeated doesn’t make them great fighters or even good ones. It makes them fighters who can get well paid for being fed to genuinely good fighters.

Here’s an example of how that works. A promoter/matchmaker/agent/manager/trainer and occasional South Carolina boxing commissioner named Bobby Mitchell cautiously moved along a smallish white heavyweight named Donald Steele during the 1990s. Under the radar in the navigable Southland, he got him to 41-0 (1 NC) with 41 knockouts. 41-0 with 41 knockouts sounds impressive. And it was impressive. It was impressive that Bobby Mitchell was able to accomplish it with someone like Steele.

Steele was being fattened up for either George Foreman or the eternally comebacking Mike Tyson. Somehow those fights never happened. Bad timing, most likely, since Foreman fought two other guys—Jimmy Ellis (16-0-1 with 15 knockouts) and Crawford Grimsley (20-0 with 18 knockouts)—whose careers followed paths much like Steele’s. Peter McNeeley was likewise brought along similarly to Steele, and he’s the one who wound up with the Tyson jackpot fight.

Steele had to settle for going over to Denmark to fall down for Brian Nielsen, which wasn’t a bad consolation prize. Nielsen was a cottage industry for obliging American heavyweights who were either ex-champions coming to the ends of their time in boxing (Larry Holmes, Tim Witherspoon, Tony Tubbs) or opponents with gaudy records and no skills. Holmes, who had his pride, lost, but only by a robbery decision. Witherspoon and Tubbs, hurting for money, made the trip to Denmark, where each suffered an uncharacteristic knockout defeat.

So the equation that undefeated equals great isn’t universally true, and it can’t be used as a measuring stick for quality. Ironically, being undefeated is often an insiders’ signal that a fighter is lousy. Zero losses represents both an invitation and a price tag.

In Mayweather’s case, being undefeated means a good deal, but not nearly enough, on its own, to vault him into the upper tier all-time great category. Former minimumweight and light flyweight Ricardo Lopez went undefeated in 52 pro fights (there was one technical draw with Rosendo Alvarez, whom Lopez beat in an immediate rematch). Lopez, who retired in 2001, never lost a fight in his life, amateur or pro, and never won a questionable decision. Although he was a better fighter in every respect than Floyd Mayweather, no case has ever been presented that he was the greatest fighter of all time, and none should be. Lopez always held that Julio Cesar Chavez was Mexico’s finest fighter. Using Mayweather’s standard of measure, there’d be an argument that Chavez, when he was 87-0, really was the greatest fighter of all time. Presumably that would have stopped being true the moment he lost to Frankie Randal a couple of fights later, again using the Floyd Mayweather barometer for determining greatness.

History

How would the Floyd Mayweather, Jr. we’ll see on May 2nd against Manny Pacquiao—exactly as he is, not as how he would have been thrust into different circumstances, where his training and options would have been much different—have fared if he could be transported to tougher times? Where in the group would one place him?

He’d go somewhere in the upper third, or possibly a bit higher. He definitely belongs; he’s good enough to factor into the mix in any era. He’ll make the IBHOF in his first year of eligibility. There’s no question that he should. But he’s nowhere near being a top-tier all-time great.

To put some perspective on it, at lightweight, he has no business being mentioned in the same breath as Joe Gans, Benny Leonard, Henry Armstrong, Ike Williams, or Roberto Duran, all of whom would probably have knocked him out. The same can be said of him at welterweight when placed against Ray Robinson or Mickey Walker, both of whom would also have knocked him out. But six of these seven guys are among the top 10 fighters of all time (and the one who, arguably, isn’t—Ike Williams—had to throw fights at times, and is still probably in the top 20).

Ike Williams vs. Ronnie James, 1946. Photo via AP

One more comparative measure of all-time greatness: it has taken Floyd Mayweather nearly 19 years to get to 47-0. In two years, 1919 and 1920, middleweight Harry Greb went 45-0, beating a number of guys who were better than anyone Mayweather has ever faced. Greb died at 32, having had 298 recorded fights. Among his victims was Gene Tunney, who would become the heavyweight champion by beating Jack Dempsey, who he would again beat in their rematch.

If we move off the greatest of the greats (against whom no one had a chance), we encounter the greats who can be seen as mere mortals.

During the days of my boxing youth in the early ’60s, Mayweather would have had to contend with Emile Griffith and Luis Rodriguez at welterweight, both of whom would have beaten him every time they fought. They were too strong, too experienced, and much too aggressive for him to have defended against. If Jose Luis Castillo and Marcos Maidana troubled Mayweather, Griffith would have walked right through him. And Rodriguez wasn’t just much busier than Mayweather, he also did everything better. Losing to these two is no embarrassment; both were great fighters. And I think Mayweather would have lasted the distance with both, although it’s hard to imagine him hearing the final bell against Thomas Hearns.

None of this is meant to denigrate Mayweather. He learned from the ground up. As much a creation of his own media manipulation as he’s been, there’s nothing about him as a boxer that isn’t entirely real. Aside from what he says about himself as a fighter, there is no smoke and mirror artifice. He can fight.

How Saturday Night’s Fight Should Go, Along with a Caveat

The Floyd Mayweather, Jr. vs. Manny Pacquiao fight should—and probably will—be a relatively straightforward boxing exhibition by Floyd, using Manny’s aggression and occasional recklessness to his own advantage in order to secure a wide-margin win on points. But with nearly a billion dollars changing hands in various ways, and the lure of as much or more for a rematch, it’s important to understand that the result that makes the most economic sense—a controversial decision win for Pacquiao—only requires somehow getting two judges on your side. The standard approach to doing this is to bring in a ringer who slips in and out of town for the night, and to add in the services of a well-respected local judge —one with whom you’ve done business for years, who understands what side the bread is buttered on, and whose ongoing ability to get further high-end calls is contingent on coming up with the desired result.

Charles Farrell has spent most of his professional life moving between music and boxing (with a few detours along the way). He has managed five world champion boxers and has 30 CDs listed under his name. Farrell is currently at work on a book of essays about music, boxing, gangsterism, and lowlife culture; a boxing anthology edited by Mike Ezra and Carlo Rotella; and a TV series, Red House, based on events from an earlier part of his life. He can be found on Twitter at @cfarrell_boxing.

Image by Jim Cooke, photo via Getty