Billy Paul got NFL Sunday Ticket this year. It was the only way to watch his Patriots every week. Paul lives in Massachusetts. See a problem?

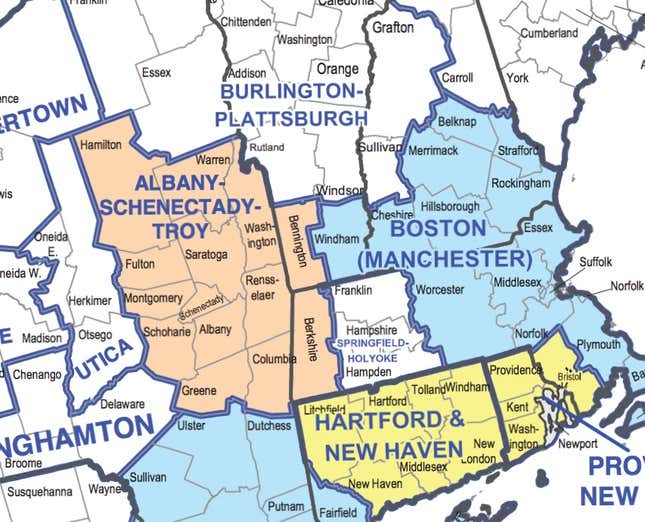

Paul, like the roughly 127,000 other people living in the Berkshire region of western Massachusetts, is a part of the Albany, N.Y., media market—the result of outdated restrictions imposed by the Federal Communications Commission based on geographical service boundaries drawn by Nielsen at the dawn of the age of television. Those lines have made it so this rural part of the Bay State is disconnected from the rest of the commonwealth. This means that while Paul and other cable customers in the Berkshires are guaranteed to see one or more games with the Jets, Giants, or even Bills every week, there’s no such guarantee that they’ll see the Patriots.

“One would think,” Paul told me, “that between all the fabulous technological advancements within global satellite positioning, Amazon delivery systems and social media pinpoints, ‘local’ broadcasting networks would know that Western Mass is in fact not in New York state!”

Paul’s right. There’s no logical reason for the market restrictions in this day and age. The technology exists, and has existed for some time, to provide any local station to anywhere in the country. But due to FCC regulations and a lack of motivation by the commission to do anything about them, cable service providers have left the Berkshires and regions like it behind. And most everyone is powerless to do anything about it.

Andrew Russell, a member of the communications team for Spectrum, told Deadspin in an email that “cable and satellite providers do not have any say in what NFL games broadcast channels choose to carry.”

NFL spokesperson Brian McCarthy told Deadspin in an email that the league is looking into ways to address the discrepancy between what people can watch and what they want to watch. “We have been conducting research on where Sunday regional games are mapped and what teams fans in those markets consider favorites,” he said.

McCarthy acknowledged that the problem is largely out of the NFL’s hands: “Outside the primary markets, it’s a network programming decision.”

The problem isn’t unique to the Berkshires. It even has a name, “orphan county,” referring to those parts of the country in which residents don’t receive in-state programming because of their media market. And there are quite a few orphan counties, according to J.P. Kirby of 506 Sports, who compiles NFL viewing maps.

“Much of western Wisconsin only gets Minnesota TV,” Kirby explained in an email. “Central New Jersey gets NYC or Philly, but rarely both; parts of east Texas get TV from Shreveport, which means they get Saints games over the Cowboys.”

“Parts of Ohio get TV from West Virginia,” Kirby added, “and they always air Steelers games over Browns or Bengals (though that might not be a bad thing!)”

The boundaries are based on Nielsen’s designated market areas, or DMAs. The areas are based on an “objective criteria,” said Nielsen spokesperson Gorki Delossantos. The markets are only changed when enough consumers tune to stations outside of their market—called “tuning share.”

“We objectively assign counties based on tuning shares over the previous four surveys—we do not assign counties based on which stations TV households may wish to view,” said Delossantos.

Delossantos stressed that Nielsen doesn’t make decisions on which channels are offered by cable providers to subscribers. That, he said, is up to the providers and the federal regulations that govern the business.

“The concept of orphan counties comes from an outdated federal policy that directly exacerbates the feeling of detachment in this part of the state,” said Adam Hinds, the Democratic state senator who represents the Berkshires as part of the commonwealth’s First Senate District.

Hinds told Deadspin that while missing football games is frustrating, it’s not the whole picture—more a symptom of a larger problem. Because of the market area, Hinds explained, citizens in the Berkshires aren’t informed on the issues their representatives are voting on in Boston.

“It’s a civic engagement issue,” said Hinds.

Cable companies in the Berkshires used to carry the Hartford, Conn. affiliate of CBS. That allowed for football and news more relevant to the east of the region. But, Kirby told me, “as FCC [regulations] and cable contracts changed, a lot of these duplicate stations were dropped, leaving only one affiliate of each network—which often don’t show the ‘right’ NFL games.”

“Until the last 10 years or so, it was common for cable companies in areas like this to carry multiple affiliates of the same network,” said Kirby.

After reviewing policies surrounding orphan counties, the FCC said in June 2016 that relaxing restrictions within the boundaries would cause too much disruption to the industry. And even if the boundaries were changed, the FCC said at the time, there would be no guarantee that receiving in-state channels would lead to more local news and community coverage.

The current record indicates that departing from the existing Nielsen DMA market determination system would create enormous disruptions in the video programming industry disproportionate to any benefit gained, and would be unlikely to increase the amount of local programming available to viewers as a whole. Furthermore, changing the market of a particular county from one DMA to another that is potentially composed of counties from the same state as the county may not necessarily increase the amount of local programming that the county receives due to the economics of broadcast television and the ability (or inability) to serve a geographically distant, but in-state county.

FCC Senior Communications Advisor Neil Grace told Deadspin in an email that there is an internal process to move market boundaries, though it requires proving that the community being served is not being provided local coverage by the stations it would lose.

“Through this process, the Commission considers whether the change would better serve the interests of the local community,” Grace said.

Grace also pointed Deadspin to comments made by then-commissioner and now-chairman Ajit Pai in March of 2015, in which Pai expressed support for changing market boundaries to provide more relevant news and information to out-of-state communities. “I look forward to hearing what the public has to say,” Pai wrote in his statement, “and am hopeful that we ultimately make it easier for satellite and cable subscribers to watch the news they care about.” Nothing’s changed, though, for western Massachusetts.

It’s not just the FCC’s market areas that are at issue, however. As Lee Fang reported at The Intercept in October, local programming just isn’t a priority for broadcasters and providers. Broadcasters argue that “social media renders local stations an anachronistic requirement of the past,” wrote Fang, and that has led to further deregulation of the way that media conglomerates provide access to local news and information for the public. That opening has provided the opportunity for new television powerhouse Sinclair Broadcasting to step in and provide right-wing propaganda disguised as local news to over 200 stations across the nation.

There’s always the chance of federal action to act as a quick fix to the problem, though it’s unlikely in the current political climate. The region’s congressional delegation is nonetheless pushing forward with an attempt to convince the commission to implement a change. In a letter to Ajit Pai, senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey and Rep. Richard Neal urged the FCC chairman to take action on the markets to provide more access to Berkshire consumers and to dispose of the archaic rules. And the Patriots figured prominently into their argument.

“The Patriots can typically be seen in New England on Sunday afternoons on either CBS or FOX,” the letter read, “that is unless you are watching in Berkshire County where viewers may only have access to New York based stations airing conflicting Bills, Giants or Jets game broadcasts instead.”

The letter went on to describe the situation as “regional disenfranchisement” in which Berkshire consumers are “subject to (and paying for) content that is of little or no interest to them.” (Local broadcasters in Albany did not return requests for comment on their programming.)

In the Berkshires, the lack of any access to Massachusetts sports and news has only added to a feeling of disconnection from the rest of the state. “The longtime issue of the Berkshires being a forgotten part of Massachusetts continues to this day,” said Kameron Spaulding, a public relations professional from the town of Lenox. “The fact that we are left in the Albany market is just another example of that very problem.”

“Is being able to watch a football game that important? No it isn’t,” said Spaulding. (Though Hinds, the state senator, said that he’s most likely to hear from his constituents about the issue when they can’t watch a Patriots game.) “But it serves as another signal of the disconnect in the state.”

“The fact that Berkshire County remains in the Albany media market shows a total lack of concern and regard for the people of Berkshire County,” said Rep. Tricia Farley-Bouvier, a Democrat from the city of Pittsfield.

Farley-Bouvier has no time for any explanations from the cable companies or the FCC that seek to shift blame for the level of access the Berkshires has to the rest of the state, she said. The treatment is only adding to the sense of alienation of many in this rural region. “There is simply no justification that we cannot access news and our own sports team.”

Eoin Higgins is a writer from western Massachusetts. You can keep up with his work by following him on Twitter.