Every birthday I get an overseas call from my grandma, always early in the morning due to time zones. This was the first year that call was tinged with concern that I would be attacked by a fellow citizen. She lived in America for decades, but suddenly, in 2017, she’s concerned about her grandson’s wellbeing.

That fear was born fresh in the last few weeks: On February 22, a man in Olathe, Kansas, killed one Indian named Srinivas Kuchibhotla, and wounded another, Alok Madasani. The killer was reportedly proud to have shot “Middle Eastern men.” On March 3, in Kent, Washington, a Sikh man was shot in his driveway, by a man who told him to “Go back to your country.”

Those are the certain ones. Also last week, Harnish Patel was shot to death in his front yard, in Lancaster, South Carolina, in circumstances that are still unexplained. It makes sense to fear the worst. Less than two months into the presidency, even when brown people aren’t being killed, they are being detained in airports or on the streets of their hometowns. Families are being surveilled at the park, like zoo animals, by resentful Americans on a crusade to “save American information technology jobs.” Anxieties—often of a flavor quite familiar to other minority groups in America—have now taken hold of Indian minds, both stateside and back over there. One victim’s father begged Indian parents to stop sending their children to the United States.

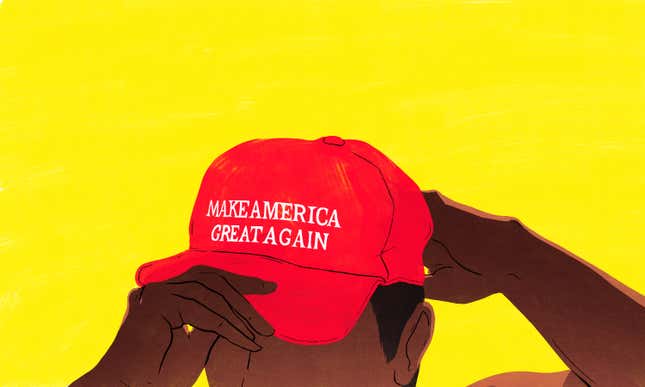

If it seemed obvious to you that electing Donald Trump would stir up a political climate less hospitable to brown people, the same could not be said for everyone. Although many themes mystified me as I talked to dozens of Hindu-Americans who supported Trump, it was this refusal to worry that made me feel the people I was encountering had lost all traction on reality.

Even back then, weeks before the election, the country had seen an upswell in racially motivated crimes. So I presented some version of this to every brown-skinned Trump supporter I spoke to:

If someone is bigoted and hateful enough to want to hurt a Muslim merely for being in their country, how can you expect this person to know the difference between you and a Muslim? In his eyes, you’re both brown. How can you trust such a person to pick the “correct” target for his resentment? Why doesn’t the current political climate—provoked by the candidate you support—make you feel less safe?

They offered me dust-dry laughter and glazed-over stares, but most of them stubbornly stayed the course. Once I was met with a competing appeal to safety: Trump would ensure the safety of all the American people by being tough on Islamic terrorism. Another man told me that Hillary also had white nationalist supporters, not just Trump, so it would be unfair to heap all the blame on his camp. Another man told me his Muslim friends were extremely concerned about the Trump presidency, but this did not make him second-guess his support at all. Not once did my point register on their faces as an actual concern.

The informal theme of the Trump rally was Islamophobia, the unspoken principle that Hindu nationalism and white nationalism could make common cause against a Muslim threat; despite their differences, Trump and the rally attendees had in common the habit of savoring every syllable in the phrase “radical Islamic terror.” (There were other minor themes—I saw plenty of “Trump For Faster Visas” signs—but the Trump presidency has been no kinder to those hopes: Starting in April, H1-B visas, exactly the sort that highly skilled engineers from India would use to work in America, will be much harder to come by, thanks to one of Trump’s first executive orders.)

Given this backdrop, I didn’t expect the Indian-Americans rallying for Trump to have much concern about the danger of their Muslim peers being attacked. But I was baffled that they couldn’t summon enough instinct for self-preservation to consider that the people lashing out won’t always pick out their Muslims correctly.

By taking the cynical gamble to cast their lot with the American xenophobes, the Hindu Trump supporters were making a strange leap of faith, that the America First crowd would suddenly become sensitive to distinctions it had previously ignored, sometimes fatally, as in the 2012 massacre at a Sikh temple in Wisconsin. Most people would be reluctant to bet their own safety on this premise—as the white guy gets angrier and emboldened, his racism gets more precise and nuanced—but some went ahead and did it anyway.

Even as local fears grew big enough to spill overseas and onto my grandmother’s television screen, some wealthy political organizers in the Indian-American community have stayed optimistic. One has gone so far as to praise the President for his leadership in the wake of these crimes. This was the tack chosen by Shalabh Kumar, organizer of the Trump rally I attended, co-chairman of the Republican Hindu Coalition (along with Newt Gingrich), Trump mega-donor, and surrealist filmmaker.

Kumar was infuriated by the Kansas shooting, calling for the death penalty:

“Pepe-trator” was a typo eerily apt for the moment, but in any case, Kumar was still heated three days later:

Eventually he found some solace in Trump’s clear leadership on this issue:

While Kumar is up there groveling before a spokesperson’s remark, let’s consider the sum total of Donald Trump’s comments on the incident, neatly contained in his speech to Congress last week:

While we may be a nation divided on policies, we are a country that stands united in condemning hate and evil in all its forms.

You’re more likely to hear Arnold Schwarzenegger’s name out of Trump’s mouth than the name of any victim of racially motivated violence. You’d sooner hear him defusing concerns over anti-Semitism by suggesting that “sometimes it’s the reverse.” But I’m glad Kumar remains convinced Trump is the guy to steward the Indian-American community in a time that’s seen four of their number shot in three weeks.

Not all of Kumar’s goals have to do with the broader interests of his community. He is also, as laid out by the Washington Post, trying to put himself in line to be the ambassador to India. You can see him regularly tagging Steve Bannon, Jared Kushner, and Steven Mnuchin in tweets that have nothing to do with them, pawing for attention. You can see him around town with his “daughter” (no blood relation), a Bollywood actress and beauty pageant winner whom he fancies his very own Ivanka, and publicly thanking Trump for asking after her, as if there were any doubts as to his policies on beautiful women. It is all very difficult to watch.

Shalabh Kumar spoke out in favor of the Muslim ban, and has yet to say a word about the visa limitation. Look at him and see the worst distillation of Hindu-American political tendencies: blinkered self-interest, alloyed with ethnic exceptionalism, marked by a desire to differentiate himself from other minority groups. Even, and especially, those groups that come from the same chunk of the globe but happen to follow a different faith. That’s well and good, so long as Kumar knows that the worst people among his American compatriots aren’t bothering to make that fine distinction. Nobody’s doing careful vetting before a hate crime; they just shoot.